By Jacob Hillesheim | Rewire

It’s history that’s relevant today: In 1882, Congress banned certain immigrants from entering the U.S. due to their race and national origin. There was no attempt to “dress up” the law. It was simply called the Chinese Exclusion Act, a title so forthright that it could be described as “bold” if that word didn’t have such a positive connotation.

“The Chinese Exclusion Act,” a new documentary premiering May 29 on PBS, examines this shameful law, the consequences of which are still felt today. I decided to explore the history of the act and how its remnants continue to play out today—you might be surprised at how much of its legacy lives on.

How the act came to be

In the late 19th century, millions of people, including well over 300,000 Chinese people, came to the United States, where another Industrial Revolution promised work for all. Some Chinese intended to live in the U.S. permanently, while others hoped to strike it rich and return home.

Even earlier, American railroad magnates had recruited Chinese workers to help build the Transcontinental Railroad. Chinese labor was so desirable that the United States and China agreed to a treaty in 1868 that encouraged Chinese immigration and promised Chinese workers freedom and equal protection of the law.

White Californians, flush with racial and economic anxiety, lobbied for anti-Chinese legislation. Congress delivered in 1882 when it introduced “An Act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to Chinese.” Although the spectacularly-named George Frisbee Hoar and his mutton chops of justice led the opposition to the bill, it still passed Congress 234 to 52.

The law was straight-forward. No Chinese “laborers,” a term interpreted as broadly as possible, could immigrate to the United States. Chinese already in the United States could not become American citizens. Finally, any Chinese who left the United States needed individual permission to return, at least until they were banned from reentering at all in 1888.

‘Driving out,’ silencing voices

The Chinese Exclusion Act kicked off a period known as “the Driving Out.” Mobs attacked and often killed Chinese residents in over 150 separate occasions all along the West Coast.

As a result, Chinese and Chinese Americans left the U.S. in large numbers. By 1920, only some 61,000 Chinese Americans remained in the continental United States. White Californians were emboldened by their “success” and extended their efforts to Japanese and Japanese Americans, culminating in the Japanese-American Internment Camps.

The Chinese Exclusion Act created a trickle-down impact on American history. It meant fewer people, less tax revenue, fewer citizens to fight or work during wartime and fewer perspectives and viewpoints, narrowing public opinion and shrinking the nation’s ability to make good decisions.

The history of the Chinese Exclusion Act also serves as a reminder that laws creating an “other” have devastating consequences for real people. Understanding how and why this un-American law came to be can perhaps help the United States avoid another one.

What you might not know is that the Chinese Exclusion Act lives on today in American law due to a pair of U.S. Supreme Court rulings.

Echoes of the exclusion act

The first full challenge to the Act’s constitutionality was Chae Chan Ping v. United States in 1889. Chae Chan Ping was a Chinese citizen who lived in the United States. In 1887, he left for China with a certificate that allowed him to return. Before he did, however, Congress passed an amendment to the Exclusion Act that banned his reentry to the United States. In a unanimous decision, the Court upheld the law.

Chae Chan Ping, in the words of Professor Natsu Taylor Saito, means that in “certain substantive areas such as immigration law the courts will not intervene because Congress and the executive–the ‘political branches’ of government–have complete power.” Whatever Congress and the president want to do with immigration, they mostly can.

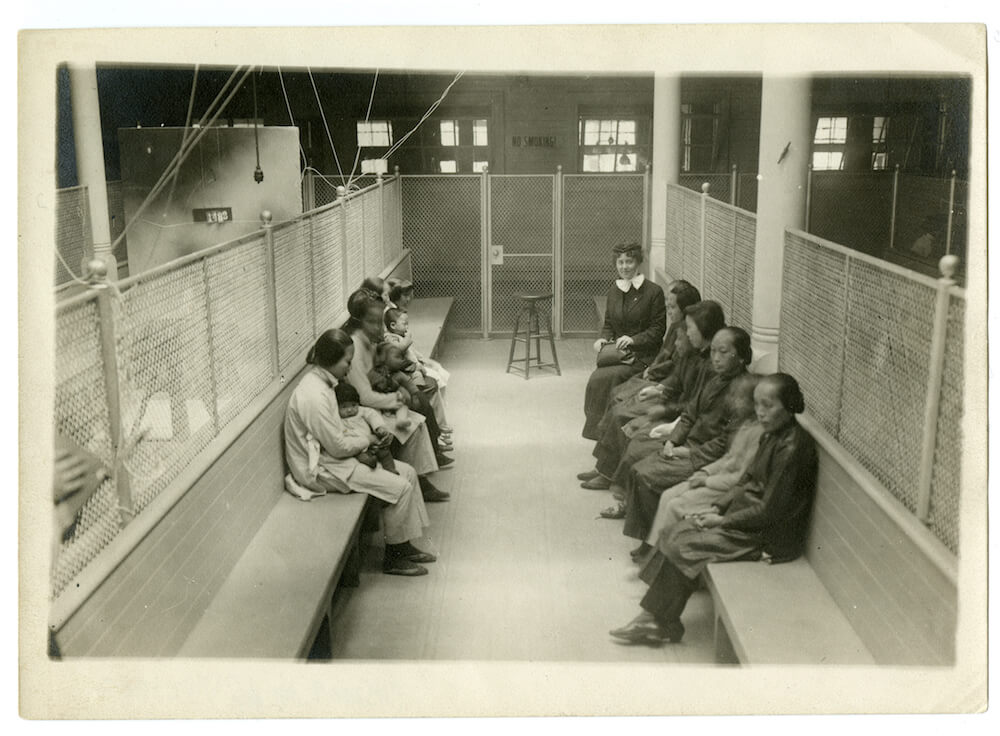

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, San Francisco, California.

Chae Chan Ping looms large in the legal debate over President Donald Trump’s travel ban. The Department of Justice has been hesitant to cite the case for obvious reasons, but University of Nevada, Las Vegas law professor Michael Kagan argues that the “validity” of the Chinese Exclusion Cases “is the central question in the challenges to President Trump’s travel bans.”

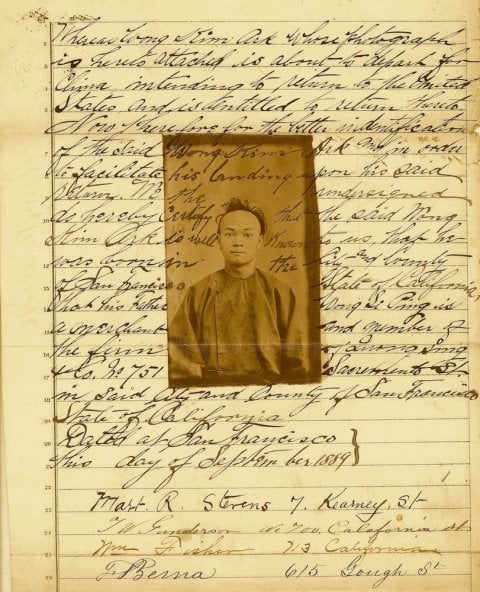

Almost a decade later, United States v. Wong Kim Ark in 1898 helped define citizenship as we understand it today. Wong Kim Ark was born in San Francisco before the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed. In 1894, Wong visited China and was denied reentry when he returned the next year.

At the heart of the case was whether Wong was an American citizen. The U.S. Supreme Court used the Fourteenth Amendment–“All persons born or naturalized in the United States… are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside”–to decide that he was. Wong Kim Arkhelped establish America’s principle of jus sanguinis, that, nearly without exception, people born on American soil are American citizens.

To better understand the law and its causes and consequences, watch The Chinese Exclusion Act on May 29 at 7pm on TPT 2.

![]() This article originally appeared on Rewire.

This article originally appeared on Rewire.

© Twin Cities Public Television - 2018. All rights reserved.

Read Next